Gold has long signified royalty and prestige. Believed to have been first used in the Bronze Age (4th-3rd Millennium BC), the precious metal was found in rivers in the form of soft nuggets, and was too malleable to be used for tools. Instead, the substance became renowned for its decorative qualities, given its illustrious shine, incorruptibility, and the ease in which it was made into alloys when combined with other metals.

Prized for its rarity – some statistics indicate that only 165000 tons of gold have been mined throughout history – much of the planet’s resources have been previously cultivated in some seminal works of art, rather than in the form of bullion sold by retailers featured on this site. In fact, Ancient Egyptian metal sifts began creating golden artworks from as early as the predynastic period. Perhaps the most famous example of Egyptian gold-work was the funeral mask belonging to Tutankhamen, seen below.

However, the use of gold in art far predates its use as currency, which occurred much later in 700 B.C. Here we list three seminal examples of gold in art history.

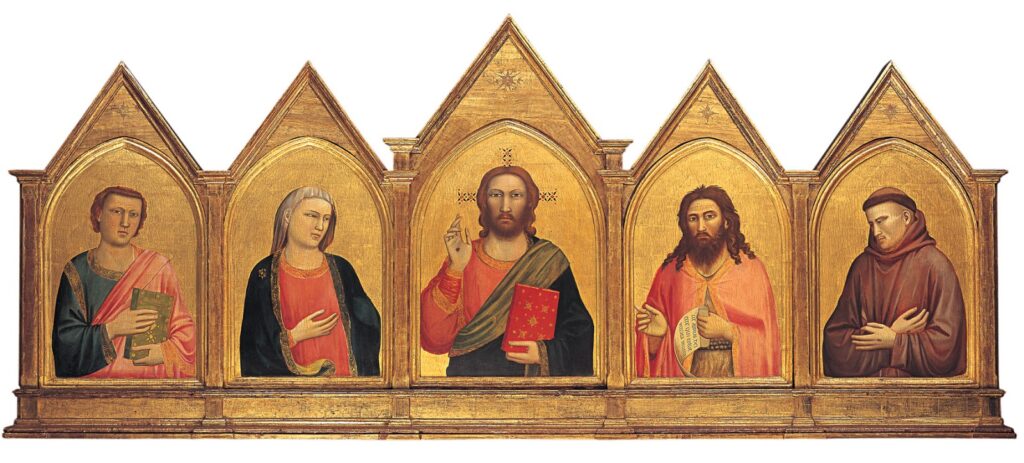

Giotto di Bondone, The Peruzzi Altarpiece, The North Carolina Museum of Art

Now located in The North Carolina Museum of Art, Giotto’s Peruzzi Altarpiece illustrates the popularity of gold leaf as an artistic medium in the late Middle Ages. Usually applied in manuscript illustration, the amount of gold leaf uses in Giotto’s altarpiece demonstrates a level of opulence suitable only for its subject matter. Religious artworks made with gold were often seen as symbolic – the illustrious nature of the substance was considered essential when rendering the divinity of Christ and his saints. Specifically, in an art historical context, gold symbolised nobility, wealth, love and justice. Yet, ironically, the bible often described the perils of lusting for gold and idolatrous golden objects of worship. Giotto therefore, utilised the substance in what was considered an acceptable way – as an aid to worship in the form of an altarpiece.

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (also called The Lady in Gold or The Woman in Gold), Neue Galerie

Inspired by the use of gold in medieval and renaissance art, the Austrian Symbolist painter, Gustav Klimt, employed gold leaf in his portraits of women. In a time that saw the increasing popularity of realist paintings and the commercialisation of art, artists were often commissioned to paint pub signs and still lives to hang in the houses of the growing middle classes. The Symbolist movement sought a return to the allegory and metaphor used in past works. For Klimt, gold was a thematic device, the substance signified romantic love and added a mystifying sensibility to his works. However, his portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I met a less than ideal fate, and was targeted amid the Nazis’ looting spree of Austria. In 1998, the Austrian government passed a restitution law, ruling that property stolen by the Nazis could be returned to its rightful owners and Maria Altmann sought to regain the Klimt paintings that were once owned by her family, including the portrait Adele Bloch-Bauer.

Pendant Reliquary Cross, The British Museum

Gold was softened when used to make jewellery. Pure gold, of 24 carats, was utilised due to its malleability and adaptability, as it is easily alloyed with other base metals, and so, produces various effects, often which compliment the gemstones that they encase. Some of the most prominent examples of gold jewellery in art history appear in the form of medieval reliquaries. Reliquaries were used to encase religious relics, often bone fragments of saints, or memorabilia relating to the life of Christ. Found in the ruins of the Great Palace of Constantinople, the pendant reliquary cross show above, is made of gold and decorated with multicoloured cloisonné enamelwork. The artefact opens to reveal an area that would have held an important relic, possibly a fragment of the cross, given the extraordinary quality of the craftsmanship. In its original setting, the opulence of the reliquary would have been considered a means to enhance the holiness of the relic itself, thus increasing its faculty as an aid to prayer, and a vehicle to perform miracles.